PRESS REPORT

|

South Florida

Sun-Sentinel

|

May 1, 2004

|

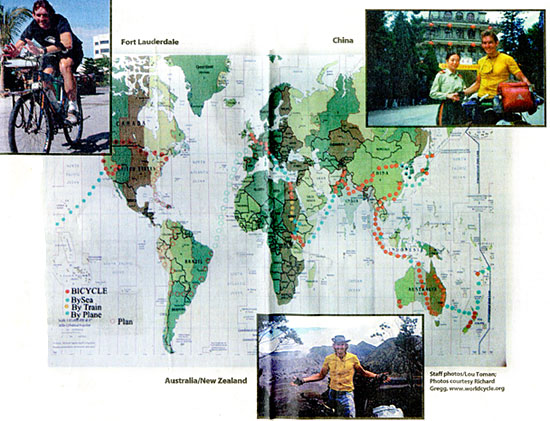

All Over the

Map

British cyclist has pedaled 34,000 miles and crossed

five continents on an epic journey around the world.

|

By MARGO HARAKAS

Staff Writer |

|

| Cyclist is aiming to meet

up with his wife soon |

Richard Gregg was startled awake

by what he thought was nearby gunfire. In Tarizania on a five-day

tenting safari, he'd spent the day in spectacular ecstasy, observing

and photographing lions, hippos, baboons and "funny little families

of warthogs running along, straight like a train, with their tails

sticking up."

Now, in the middle of the night, outside his tent, issued a loud and unfamiliar crack. Cautiously, he peeked out the tent flap.

"I saw a hyena, silver in the moonlight, at our fire pit, cracking chicken bones in his jaw," he says, laughing at the recollection.

A perfect ending, and diary entry, for another adventurous day. Yet a mere footnote (and brief side trip) to Gregg's epic adventure--bicycling around the world. For more than 13 years, the 40 year old Brit, who has a bachelor's degree in engineering, has been at it. He's logged more than 34,000 miles on foot power alone, crossing five continents and 38 countries. Florida is his 27th state.

He has stood in awe before the Taj Mahal, struggled across the Himalayas, contracted a variety of illnesses, married and still pressed on.

After wearing out one 21-speed mountain bike and a couple dozen tires ("I replace a pair about every 3,000 miles"), the end of his quest is in sight. A roll through the Caribbean and South America, then passage across the Atlantic and he's home.

"I want to see the Amazon and the Andes yet," Gregg says during a stopover in Fort Lauderdale. With money running out, he hopes to complete the circuit back in Sheffield, England, in perhaps as little as three months. He is eager to reunite with his wife, Haruyo, who awaits him in her homeland of Japan. They met in Laos and married three years ago in June in New Zealand. They were together only a year before Gregg resumed his bike trek. For a couple of months, Haruyo traveled with him until the cold and rainy weather did her in. "She was miserable," Gregg says. "She decided to let me finish alone."

Since age 8, when he copied from the encyclopedia a picture of the Taj Mahal, Gregg had harbored the dream of seeing the world, not in small isolated pieces but in its full, grand sweep. "I don't know what possessed me. I'd hardly been anywhere before doing this," says the soft-spoken, " 6-foot-2 cyclist. "I didn't even own a bike until I was 14 years old."

Even more amazing, his adventure commenced barely a year after Gregg underwent major back surgery. "I was like an old man. I couldn't do anything without pain. Sitting, lying down, it was always there," he says. "I thought I'd be going around the world in a wheelchair."

After the surgery, doctors informed him that 10 years hence he most certainly would be suffering from arthritis of the spine. "I don't always believe what doctors tell me," he says dismissively, still free of pain even when he rides 125 miles in a day.

The Guinness Book of Records, says Gregg, defines a trip around the world as traveling at least 16,500 miles, crossing four or more continents, and beginning and ending in the same place. Mileage-wise, he notes, "I've already ridden more than twice that."

On the road, Gregg carries about 200 pounds of gear, including clothes, dehehydrated food, water, tent, stove, pots, sleeping bag and mat, notebooks and journals (wrapped inplastic), cameras and slides.

He's financing his journey primarily with moneyu earned while teaching English in Japan for 2 1/2 years, from 1994 to 1997. From time to time, he'll grab a day's work here and there.

In New Zealand, "I did some engineering stress calculations for a friend with a boring company," he says. He also earned a fewbucks on an onion farm cutting up onions looking for parasites. In Singapore and Hong Kong he he landed a job as a film extra. In Canada, he spent an afternoon screwing bolts into a sewage containment tank.

Gregg has interrupted his journey to return home to Sheffield only a handful of times: for a family wedding, a birth, and medical treatment for an injury sustained in Kashmir.

"I'd cycled 7,000 miles to get there [Kashmir] on some of the most dangerous roads known to man," he says, only to be injured in an awkward accident. He fell through the maintenance hatch on a houseboat.

The question, of course, is why is he doing this. "There are so many reasons," he says. "The most important is to meet the people of the world. I didn't trust TV to bring me the world. There are things out there I have to see. I want desperately to see."

At times he's wondered if he'd make it. Struggling through the Himalayas, he thought he might be drawing his final breath. "I was slumping over the handlebars, gasping for oxygen." The map showed the pass at 17,000 feet and he had at least another 20 kilometers to go. But the map was wrong. "I was at the top of the first pass," he says. "Nothing after that was as hard."

He also had doubts when laid up by dysentery, typhoid or some other exotic ailment. But once well, he'd bounce back on the bike, thinking, "No point in giving up now."

As for dangers, he says, "I think safety is an illusion. The more you wrap yourself in cotton wool, the more dangerous life becomes. You have to take certain risks to enjoy life and live to the fullest."

Which explains why Gregg chose to join a party tracking rhinos through a bamboo forest in the Chitwan National Park in Nepal. He knew full well a charging rhino can be deadly. Foolishly, he hoped the rhinos would take no notice. When one turned around and started advancing in his direction, his guide beat the ground with a stick and hollered until the rhino retreated.

In towns and villages, the near misses were of a different nature: Receiving a glancing blow by a passing car, having a passenger on a bus try to grab his cap ( forcing the cap to slip over his eyes, temporarily blinding him), and being nearly driven off a bridge when another bus rider grabbed his arm.

The North American leg of his journey began in April 2002. He stepped ashore in Oakland, Calif., after a two week voyage across the Pacific on a container ship. The cost of his passage--$86.50. "All I had to pay for was my food," he says. And for that, he got "the owner's cabin."

He eventually pedaled his way northward into Canada (where his bike frame broke and a good-hearted soul fixed it free) and then down the East Coast, where earlier this year, "I dipped my toe in the Atlantic for the first time since September 1990," when his quest began.

In Connecticut, he was drenched in freezing rains. In Maryland, Pennsylvania and New York he continued to brave single-digit temperatures, spining onward even when covered in a layer of ice. "My toes were freezing. I couldn't feel them or my fingers, either. My nose hairs froze. I'd go for a couple of hours and then take a break and have a hot drink, warm up and start out again."

In April, he hit South Florida.

|

| Many Many Miles Logged: Richard Gregg

keeps a diary of his adventures over the last 13 years. "There

are things out there I have to see, I want to desperately

to see," he said during a stop in Fort Lauderdale. Staff

Photo/Lou Toman |

After nearly 14 years of global exploration, he concludes there

are some sights everyone should see at least once: the wildlife

in Africa, the Himalayas, the world's great coral reefs. "And if

it had to be one country, it would be India"not necessarily because

it's a livable place, but because it has everything in the extreme,

from wild elephants and tigers to deserts and rain forests and beaches.

And the culture is just so diverse."

Gregg's journey, however, has been as much about self-discovery as territorial discovery. He has proven to himself and others he has the ability to persevere, even when lonely, despondent, sick or injured. "The most difficult part is being away from my wife." It was easier when he was unattached. Now his thoughts are increasingly about "stopping and being with her."

But, he quickly adds, "It's not really an option." He made himself a promise: "No matter what, no matter who, I'd never give up this journey. [It] would leave me incomplete." An aborted journey would also, he believes, ultimately strain the marriage. The benefit to Haruyo is "she'll always know I'm going to do what I say I'll do."

He ends his circumnavigation with a new way of looking at life, wanting to find "even in the most mundane aspects" of life, "that which is unusual and beautiful. I want to treat it all as though I won't see it again," he says.

He hopes to reach England by midsummer. "But it's so variable. If I find a ship going to Portugal from Brazil, I'll probably take it."

He'll meet up with his wife eithger in England or Japan. "We'll probably live in Japan."

He plans to write a book about his travels, possibly open a phot gallery in Osaka, and become a teacher.

|